afrom Dhamma Musings, Saturday, February 4, 2012

Animals played a role in several events in the life of both the historical and legendry Buddha. Usually their appearance is incidental – the white elephant in Mahamaya’s dream, and the steed Khantaka carrying Prince Siddhattha away into the night, being examples of this. In a few other incidents they play a more important role – Prince Siddhattha rescuing the goose from Devadattha, the Buddha being looked after by an elephant (and a monkey according to the commentary) during his stay in the Parileyya Forest, and his calming of the infuriated elephant Nalagiri.

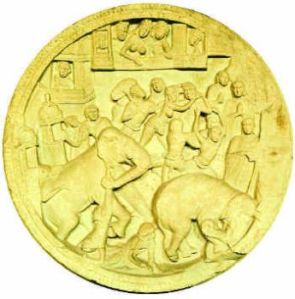

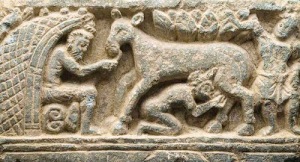

This last story has long been a favourite with artists and the earliest depiction of it is to be found on a a medallion from the railing of the Amaravati Stupa built in about 200 CE. The sculptor shows the elephant first charging and then bowing before the Buddha, thus giving a sense of movement. The terrified onlookers are realistically depicted highlights the drama of the scene. The next piece is a carved 4th century CE fragment from Gandhara showing the Buddha stroking Nalagiri’s head, a detail mentioned in the Tipitaka account of the story. Likewise the people watching from the balcony above are specifically mentioned in the text. The third picture is an illustration of the same incident from a 19th century Thai manuscript.

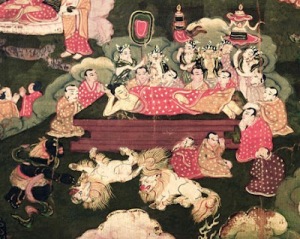

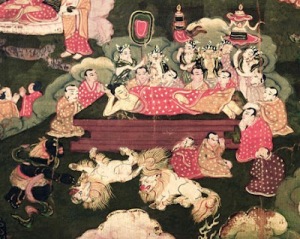

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, some of those gathered around the Buddha broke into tears when he died while others remained composed. Such people usually appear in depictions of the Buddha’s passing. In Japan however, artists illustrating this event often included animals amongst the mourners. I’m not sure why this is so but it is probably because the Mahayana Maraparinirvana Sutra says that ‘all beings in the Triple World wept and wailed’ as the Tathagata passed away. This gave artists the opportunity to use their skill and their imagination to paint a wide variety of beautiful and interesting animals. The first picture below is of a 16th century (Monoyama Period) scroll painting. The next picture is an enlarged section of a similar depiction of the Parinibbana from around the same time. It is clear that the artists delighted in the painting creatures as diverse as centipedes, crabs and molluscs as well as several mythological beasts. The third picture, from a Tibetan thangka, shows two snow lions (gang shenge) morning the Buddha’s passing, an element unusual in Tibetan art.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, some of those gathered around the Buddha broke into tears when he died while others remained composed. Such people usually appear in depictions of the Buddha’s passing. In Japan however, artists illustrating this event often included animals amongst the mourners. I’m not sure why this is so but it is probably because the Mahayana Maraparinirvana Sutra says that ‘all beings in the Triple World wept and wailed’ as the Tathagata passed away. This gave artists the opportunity to use their skill and their imagination to paint a wide variety of beautiful and interesting animals. The first picture below is of a 16th century (Monoyama Period) scroll painting. The next picture is an enlarged section of a similar depiction of the Parinibbana from around the same time. It is clear that the artists delighted in the painting creatures as diverse as centipedes, crabs and molluscs as well as several mythological beasts. The third picture, from a Tibetan thangka, shows two snow lions (gang shenge) morning the Buddha’s passing, an element unusual in Tibetan art.

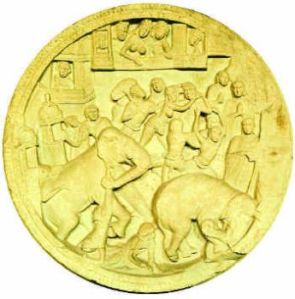

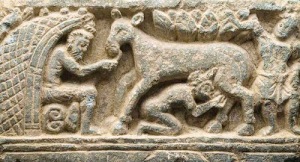

After the biography of the Buddha himself, the Jataka stories have long been most Buddhist’s main knowledge of and contact with the Dhamma. Consequently there are numerous depictions of Jatakas in the art of all Buddhist cultures, and they are depicted in the earliest Buddhist art. The first picture illustrates the Mahakapi Jataka (No.407) in which a monkey king risks his life, and eventually looses it, to save his troop. The piece is a medallion from the Barhut Stupa dating from about 150 BCE. Being one of the earliest examples of Buddhist art the treatment is naive and awkwardly conceived but the story it illustrates would have been immediately identifiable to the viewer. The Alambusa Jataka (No.523) tells of a doe who falls in love with the ascetic who shared her forest. One day he urinated in the river, passing out semen as he did so, the doe later drunk from the river, became pregnant and in time gave birth to a boy. The kindly ascetic accepts the child as his own and helps bring him up. A sexual misadventure in the boy’s subsequent life and his father’s advice concerning it makes up the core of the story. The ascetic, the doe and their child are depicted in a panel from northern India dating from the 4th-5th century CE. Below this is a painting from Dunghuang Cave in western China dated 450 CE depicting the Nigrodhamiga Jataka (No.12). In this story a stag’s willingness to give his life to protect his herd from a king’s frequent hunting expeditions, moves the king to give up hunting and eventually, at the stag’s request, to ban all hunting throughout his realm. The final picture is an illustration from an early 19th century Thai manuscript of the Vessantra Jataka (No.574). It shows Vessantra on his wondrous rain-making white elephant which he is about to give away.

After the biography of the Buddha himself, the Jataka stories have long been most Buddhist’s main knowledge of and contact with the Dhamma. Consequently there are numerous depictions of Jatakas in the art of all Buddhist cultures, and they are depicted in the earliest Buddhist art. The first picture illustrates the Mahakapi Jataka (No.407) in which a monkey king risks his life, and eventually looses it, to save his troop. The piece is a medallion from the Barhut Stupa dating from about 150 BCE. Being one of the earliest examples of Buddhist art the treatment is naive and awkwardly conceived but the story it illustrates would have been immediately identifiable to the viewer. The Alambusa Jataka (No.523) tells of a doe who falls in love with the ascetic who shared her forest. One day he urinated in the river, passing out semen as he did so, the doe later drunk from the river, became pregnant and in time gave birth to a boy. The kindly ascetic accepts the child as his own and helps bring him up. A sexual misadventure in the boy’s subsequent life and his father’s advice concerning it makes up the core of the story. The ascetic, the doe and their child are depicted in a panel from northern India dating from the 4th-5th century CE. Below this is a painting from Dunghuang Cave in western China dated 450 CE depicting the Nigrodhamiga Jataka (No.12). In this story a stag’s willingness to give his life to protect his herd from a king’s frequent hunting expeditions, moves the king to give up hunting and eventually, at the stag’s request, to ban all hunting throughout his realm. The final picture is an illustration from an early 19th century Thai manuscript of the Vessantra Jataka (No.574). It shows Vessantra on his wondrous rain-making white elephant which he is about to give away.

The Buddha taught that there are six realms of existence, one of which is the animal world. (tiracchana yoni). All of these realms constitute samsara, the continually process of birth and death. Indian artists illustrated this doctrine diagrammatically as a wheel of six segments, each showing one of the realms. A single very fragmentary painting of the six realms survives from India, but they are common in Tibet and are painted on the walls at the entrance of most temples. Depictions of the animal world usually show a variety of creatures, domestic and wild, actual and mythological. This is a typically illustration of the animal world from a contemporary Tibetan thangka.

The Buddha taught that there are six realms of existence, one of which is the animal world. (tiracchana yoni). All of these realms constitute samsara, the continually process of birth and death. Indian artists illustrated this doctrine diagrammatically as a wheel of six segments, each showing one of the realms. A single very fragmentary painting of the six realms survives from India, but they are common in Tibet and are painted on the walls at the entrance of most temples. Depictions of the animal world usually show a variety of creatures, domestic and wild, actual and mythological. This is a typically illustration of the animal world from a contemporary Tibetan thangka. As in other religions Buddhists saw certain animals as symbolizing particular things; e.g. the lion nobility and courage, the monkey an undisciplined mind, the goose detachment, and the elephant patience and calm deliberation. They also included animals in their folk tales. One example of this is the story of the three animals who teamed up to reach the fruit none of them could reach individually and who as a result became friends. The story is unique to Bhutan although it was probably a local development of the Jataka (No.37). An animal symbol from China and Japan, and probably of Buddhist origin is the three wise monkeys, now familiar the world over. The most famous and charming depiction of these hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil creatures is found under the eaves of the on the Toshogu Temple in Nikko, carved when the temple was built in the early 17th century.

As in other religions Buddhists saw certain animals as symbolizing particular things; e.g. the lion nobility and courage, the monkey an undisciplined mind, the goose detachment, and the elephant patience and calm deliberation. They also included animals in their folk tales. One example of this is the story of the three animals who teamed up to reach the fruit none of them could reach individually and who as a result became friends. The story is unique to Bhutan although it was probably a local development of the Jataka (No.37). An animal symbol from China and Japan, and probably of Buddhist origin is the three wise monkeys, now familiar the world over. The most famous and charming depiction of these hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil creatures is found under the eaves of the on the Toshogu Temple in Nikko, carved when the temple was built in the early 17th century.

The use of animals as decorative elements in Buddhist art and architecture is as rich as that found anywhere. One of but many examples of this is the procession of animals that the ancient Sri Lankans decorated the semi-circular door-steps (patika) of their temples with. Many different animals are used and in different combinations but perhaps the most common is a continual line made up of elephants, horses, lions and bull. The elephants in these door-steps and elsewhere in Sri Lankan art are depicted most realistically. The example below from Anuradhapura dates from about the 9th century. Under the row of animals is a row of geese (hamsa) with flower buds in their beaks, a motif originating in India.

The use of animals as decorative elements in Buddhist art and architecture is as rich as that found anywhere. One of but many examples of this is the procession of animals that the ancient Sri Lankans decorated the semi-circular door-steps (patika) of their temples with. Many different animals are used and in different combinations but perhaps the most common is a continual line made up of elephants, horses, lions and bull. The elephants in these door-steps and elsewhere in Sri Lankan art are depicted most realistically. The example below from Anuradhapura dates from about the 9th century. Under the row of animals is a row of geese (hamsa) with flower buds in their beaks, a motif originating in India.

This last story has long been a favourite with artists and the earliest depiction of it is to be found on a a medallion from the railing of the Amaravati Stupa built in about 200 CE. The sculptor shows the elephant first charging and then bowing before the Buddha, thus giving a sense of movement. The terrified onlookers are realistically depicted highlights the drama of the scene. The next piece is a carved 4th century CE fragment from Gandhara showing the Buddha stroking Nalagiri’s head, a detail mentioned in the Tipitaka account of the story. Likewise the people watching from the balcony above are specifically mentioned in the text. The third picture is an illustration of the same incident from a 19th century Thai manuscript.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, some of those gathered around the Buddha broke into tears when he died while others remained composed. Such people usually appear in depictions of the Buddha’s passing. In Japan however, artists illustrating this event often included animals amongst the mourners. I’m not sure why this is so but it is probably because the Mahayana Maraparinirvana Sutra says that ‘all beings in the Triple World wept and wailed’ as the Tathagata passed away. This gave artists the opportunity to use their skill and their imagination to paint a wide variety of beautiful and interesting animals. The first picture below is of a 16th century (Monoyama Period) scroll painting. The next picture is an enlarged section of a similar depiction of the Parinibbana from around the same time. It is clear that the artists delighted in the painting creatures as diverse as centipedes, crabs and molluscs as well as several mythological beasts. The third picture, from a Tibetan thangka, shows two snow lions (gang shenge) morning the Buddha’s passing, an element unusual in Tibetan art.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, some of those gathered around the Buddha broke into tears when he died while others remained composed. Such people usually appear in depictions of the Buddha’s passing. In Japan however, artists illustrating this event often included animals amongst the mourners. I’m not sure why this is so but it is probably because the Mahayana Maraparinirvana Sutra says that ‘all beings in the Triple World wept and wailed’ as the Tathagata passed away. This gave artists the opportunity to use their skill and their imagination to paint a wide variety of beautiful and interesting animals. The first picture below is of a 16th century (Monoyama Period) scroll painting. The next picture is an enlarged section of a similar depiction of the Parinibbana from around the same time. It is clear that the artists delighted in the painting creatures as diverse as centipedes, crabs and molluscs as well as several mythological beasts. The third picture, from a Tibetan thangka, shows two snow lions (gang shenge) morning the Buddha’s passing, an element unusual in Tibetan art.

After the biography of the Buddha himself, the Jataka stories have long been most Buddhist’s main knowledge of and contact with the Dhamma. Consequently there are numerous depictions of Jatakas in the art of all Buddhist cultures, and they are depicted in the earliest Buddhist art. The first picture illustrates the Mahakapi Jataka (No.407) in which a monkey king risks his life, and eventually looses it, to save his troop. The piece is a medallion from the Barhut Stupa dating from about 150 BCE. Being one of the earliest examples of Buddhist art the treatment is naive and awkwardly conceived but the story it illustrates would have been immediately identifiable to the viewer. The Alambusa Jataka (No.523) tells of a doe who falls in love with the ascetic who shared her forest. One day he urinated in the river, passing out semen as he did so, the doe later drunk from the river, became pregnant and in time gave birth to a boy. The kindly ascetic accepts the child as his own and helps bring him up. A sexual misadventure in the boy’s subsequent life and his father’s advice concerning it makes up the core of the story. The ascetic, the doe and their child are depicted in a panel from northern India dating from the 4th-5th century CE. Below this is a painting from Dunghuang Cave in western China dated 450 CE depicting the Nigrodhamiga Jataka (No.12). In this story a stag’s willingness to give his life to protect his herd from a king’s frequent hunting expeditions, moves the king to give up hunting and eventually, at the stag’s request, to ban all hunting throughout his realm. The final picture is an illustration from an early 19th century Thai manuscript of the Vessantra Jataka (No.574). It shows Vessantra on his wondrous rain-making white elephant which he is about to give away.

After the biography of the Buddha himself, the Jataka stories have long been most Buddhist’s main knowledge of and contact with the Dhamma. Consequently there are numerous depictions of Jatakas in the art of all Buddhist cultures, and they are depicted in the earliest Buddhist art. The first picture illustrates the Mahakapi Jataka (No.407) in which a monkey king risks his life, and eventually looses it, to save his troop. The piece is a medallion from the Barhut Stupa dating from about 150 BCE. Being one of the earliest examples of Buddhist art the treatment is naive and awkwardly conceived but the story it illustrates would have been immediately identifiable to the viewer. The Alambusa Jataka (No.523) tells of a doe who falls in love with the ascetic who shared her forest. One day he urinated in the river, passing out semen as he did so, the doe later drunk from the river, became pregnant and in time gave birth to a boy. The kindly ascetic accepts the child as his own and helps bring him up. A sexual misadventure in the boy’s subsequent life and his father’s advice concerning it makes up the core of the story. The ascetic, the doe and their child are depicted in a panel from northern India dating from the 4th-5th century CE. Below this is a painting from Dunghuang Cave in western China dated 450 CE depicting the Nigrodhamiga Jataka (No.12). In this story a stag’s willingness to give his life to protect his herd from a king’s frequent hunting expeditions, moves the king to give up hunting and eventually, at the stag’s request, to ban all hunting throughout his realm. The final picture is an illustration from an early 19th century Thai manuscript of the Vessantra Jataka (No.574). It shows Vessantra on his wondrous rain-making white elephant which he is about to give away.

The Buddha taught that there are six realms of existence, one of which is the animal world. (tiracchana yoni). All of these realms constitute samsara, the continually process of birth and death. Indian artists illustrated this doctrine diagrammatically as a wheel of six segments, each showing one of the realms. A single very fragmentary painting of the six realms survives from India, but they are common in Tibet and are painted on the walls at the entrance of most temples. Depictions of the animal world usually show a variety of creatures, domestic and wild, actual and mythological. This is a typically illustration of the animal world from a contemporary Tibetan thangka.

The Buddha taught that there are six realms of existence, one of which is the animal world. (tiracchana yoni). All of these realms constitute samsara, the continually process of birth and death. Indian artists illustrated this doctrine diagrammatically as a wheel of six segments, each showing one of the realms. A single very fragmentary painting of the six realms survives from India, but they are common in Tibet and are painted on the walls at the entrance of most temples. Depictions of the animal world usually show a variety of creatures, domestic and wild, actual and mythological. This is a typically illustration of the animal world from a contemporary Tibetan thangka. As in other religions Buddhists saw certain animals as symbolizing particular things; e.g. the lion nobility and courage, the monkey an undisciplined mind, the goose detachment, and the elephant patience and calm deliberation. They also included animals in their folk tales. One example of this is the story of the three animals who teamed up to reach the fruit none of them could reach individually and who as a result became friends. The story is unique to Bhutan although it was probably a local development of the Jataka (No.37). An animal symbol from China and Japan, and probably of Buddhist origin is the three wise monkeys, now familiar the world over. The most famous and charming depiction of these hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil creatures is found under the eaves of the on the Toshogu Temple in Nikko, carved when the temple was built in the early 17th century.

As in other religions Buddhists saw certain animals as symbolizing particular things; e.g. the lion nobility and courage, the monkey an undisciplined mind, the goose detachment, and the elephant patience and calm deliberation. They also included animals in their folk tales. One example of this is the story of the three animals who teamed up to reach the fruit none of them could reach individually and who as a result became friends. The story is unique to Bhutan although it was probably a local development of the Jataka (No.37). An animal symbol from China and Japan, and probably of Buddhist origin is the three wise monkeys, now familiar the world over. The most famous and charming depiction of these hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil creatures is found under the eaves of the on the Toshogu Temple in Nikko, carved when the temple was built in the early 17th century.

The use of animals as decorative elements in Buddhist art and architecture is as rich as that found anywhere. One of but many examples of this is the procession of animals that the ancient Sri Lankans decorated the semi-circular door-steps (patika) of their temples with. Many different animals are used and in different combinations but perhaps the most common is a continual line made up of elephants, horses, lions and bull. The elephants in these door-steps and elsewhere in Sri Lankan art are depicted most realistically. The example below from Anuradhapura dates from about the 9th century. Under the row of animals is a row of geese (hamsa) with flower buds in their beaks, a motif originating in India.

The use of animals as decorative elements in Buddhist art and architecture is as rich as that found anywhere. One of but many examples of this is the procession of animals that the ancient Sri Lankans decorated the semi-circular door-steps (patika) of their temples with. Many different animals are used and in different combinations but perhaps the most common is a continual line made up of elephants, horses, lions and bull. The elephants in these door-steps and elsewhere in Sri Lankan art are depicted most realistically. The example below from Anuradhapura dates from about the 9th century. Under the row of animals is a row of geese (hamsa) with flower buds in their beaks, a motif originating in India. One Buddhist monument that depicts numerous animals, actual and mythological, in most of their roles, as participants in the Buddha’s biography, symbols, as decorative elements and in illustrations of Jataka stories – is the great stupa at Sanchi, a huge repository of early Buddhist art. Below is a small selection of these.

One Buddhist monument that depicts numerous animals, actual and mythological, in most of their roles, as participants in the Buddha’s biography, symbols, as decorative elements and in illustrations of Jataka stories – is the great stupa at Sanchi, a huge repository of early Buddhist art. Below is a small selection of these.

No comments:

Post a Comment