by Bhikkhu Khantipalo

"Who are not heedless, they

Dig up the root of suffering

By day and night give up things dear,

Deathly, sensuous and very hard to cross."

Most people in this world fall among the class of persons known as ’heedless’—and for most of their lives at that. What is this kind of person like? A heedless man, one who dwells sunk in this mud of heedlessness, does not care to develop in himself any of the virtues in this life, and instead drifts about controlled by the currents of his desires, which lead him to do all sorts of things which are evil. He does not care to develop wisdom, which in the beginning means the ability to distinguish what is skilful, profiting oneself and others, from what is evil, poisoning oneself and others. He does not call to mind that this life is a short span between birth and death and that within it lies the experience of many bitter and unwelcome things. He is lazy, making no effort towards self-control. He does not aspire to any high ideal and thinks only to get his sense-desires fulfilled. He is bogged down in the slough of materialism and selfishly grabs for himself whatever he can get out of this world. O this heedless man! How much of sufferings he makes for himself and others! He is, in other words, a man who does not know where his own good, or the good of others lies. He helps forward strife and dissension, and because he is firmly attached to possessions, relations, people and places; he can never find the happiness for which, so vainly, he looks. This heedless man is not some strange and abstract character but veritably in myself and in yourselves whenever we do not guard ourselves and make no efforts in the Dhamma-training. And we are the people who in proportion to our heedlessness suffer the thorny fruits of evil which ripen for us, and of which, though bitter, we must partake.

Therefore, this heedless man is the very opposite of the true Buddhist who is well described by the adjective ’heedful’. The quality of heedfulness has been praised many times by the Exalted Buddha, just as the opposite, heedlessness, has been condemned. In this Dhamma, there is much to be practised and there is practice suitable for every posture of the body and every minute of the day. There is practice to be done concerning the stream of thoughts racing in the mind, there is more practice connected with the thousands of words spoken every day, and there is Dhamma-practice for the body, whatever it is doing. Now none of this can be accomplished without heedfulness, without making effort, without employing mindful awareness, or without wisdom. Heedfulness implies the conscious cultivation of these three aspects of Dhamma: effort, mindfulness and wisdom. These three mark the true Buddhist, one who is really trying to practise what the Exalted One has taught. So then, by way of contrast with that heedless fellow who is our untrained and unrestrained selves, let us take a look at the heedful Dhamma-practiser, whom we may occasionally resemble. A heedful man does take care to develop in himself all the virtues according to his ability and his need, and he does not drift about from desire to desire but lays some restraint upon his mind, speech and body with regard to this. As he does so, he is able to distinguish the wholesome from the evil, and he knows clearly why certain actions are harmful while others are helpful to Dhamma-training. He is aware of the short span of this life which may at any moment, and in countless million ways, come to an end. Therefore, he is not lazy and does put forth effort towards self-control. He knows of higher ideals than mere materialism, and he does aspire to attain them for himself, thus benefiting others as well. He knows full well that to be the prey of desires all the time is the most potent way of increasing all kinds of sufferings and unhappiness. So then, he is a man who knows the good of himself and the good of others whom he can help in various ways. From the store of goodness and wisdom cultivated by him, he becomes happy and can show the way of true happiness to others. This heedful man is also no abstraction but truly ourselves whenever we see the I in our own hearts, smeared with greed, aversion and delusion, disturbed by the boiling-up of so many desires, there is much to be done. So we stir up energy within ourselves to practise Dhamma, that is, to be generous, helpful and kindly, to keep pure the Precepts, to develop the heart in calm and concentration by appropriate ways, and to wield the sword of wisdom within our hearts for the purification which should be made there; and again, through this effort, we become mindful, we become aware of the body in all its aspects, we develop awareness of feelings as they arise and pass away, we become aware of what sort of state the mind is in, and finally we know clearly the different constituents or the mind as they arise and pass away; and with this mindfulness goes wisdom and cleansing. No one can claim to be truly a Buddhist unless he is heedful, that is, he is making effort in training himself in Dhamma, to the extent possible for him.

Now we can turn to the verse spoken by the Exalted Buddha and consider its meaning for ourselves. In the first line are mentioned those people “who are not heedless” and they form the subject of this instruction. Those who are heedless are not mentioned directly but it is clear from the verses that they, whether by day or by night, do not “give up things dear” and so make no efforts to dig up the root of suffering which, as we shall see, is called craving. So these heedless people are trapped in things bound up with death, things which appeal to the senses and desires and seem to increase pleasure, thing, which are as an ocean, very extensive and perilous, which are difficult to overcome. The sufferings of the heedless will become clearer by contrast with the happiness born of Dhamma-practice by the heedful, of which this verse speaks.

This “root of suffering”—let us look into the meaning of it. Roots are commonly the tough and deeply penetrating underground parts of trees and plants. Towards their tips they are much divided and very fine, and they seek constantly for nutriment. But the root spoken of here, though it has these characteristics, is found in the heart of every unenlightened person. The root of suffering is tough, for craving and desire are not easy to pull up but strongly resist the efforts of those who try. And this craving root is certainly deeply penetrating. lt has not only been planted and grown in this life but over innumerable existences before our present birth; it has established itself in the very depths of our hearts. And this root, like others, is underground, for it cannot easily be seen. Some people are not even aware that they have any craving at all, and most people have little idea of its extent. The network of fibres of this craving become very fine, very subtle towards their ends, and even those who have long been heedful and practised Dhamma with devotion, may find it hard to root out the finest threads. But if they are not removed like twitch, bindweed or dandelions, this wretched craving springs up again. So it is that the Exalted One has said: “So dig up craving by its root”. This root of suffering called craving also seeks for nutriment of many kinds, as do the roots of plants. For instance, there is ordinary food which is craved for its pleasing appearance, its subtle aroma, its delicious taste, its delightful texture, its allaying of hunger-pain, and its way of increasing one’s sense of well being by fullness. So, in this way, craving is expressed through eye, nose, tongue and bodily sensibility. Then there is craving in the mind by thinking about the desired nutriment. Now, people “who are not heedless” look upon this craving as a parasite which has a stranglehold but must be destroyed as quickly as possible. And why do they think like this? From the clear understanding born of their not being heedless, they see that craving is the root of suffering. All the kinds of sufferings are all born of craving, or suffered because of craving. Whether those sufferings are slightly disagreeable, or whether they are very grave; whether they are physical, or whether they are mental; all kinds of sufferings are born of desires. How can this be? When one desires and gets, one suffers from keeping, from maintaining; when one does not get what is craved, one also suffers. Desires are never fulfilled entirely and if you look into this, you will find that the thing desired never quite lives up to expectations. We expect stability in the desired people or things. But neither ourselves nor those desired things whatever they are—people, places, experiences—neither subject nor object has any stability. Instability marks this world and when we grab at something desired, thinking it stable, we heap up this suffering for ourselves. Nor does a heedless man understand that unstable things are unsatisfactory or dukkha. Not living up to expectations, they disappoint him. Not being permanent or remaining in the form desired, they cannot be but unsatisfactory. That heedless fellow also has no idea about the non-self-nature of things. The most important ’things’ to explain here are the physical and mental aspects of oneself. Though ordinarily thought of as self, as belonging to self, a little reflection will prove how far from being ’owned’ this mind and body are. The heedless man never thinks whether ’my body’, ’my mind’, ’myself’ could really be true. But neither body nor mind obey a self, they just work governed by certain laws and conditions. There is no possibility of a self who is the owner of mind and body—such ideas are born of craving for security. And where there is craving, there is bound to be suffering. So this root of suffering spreads its battening rootlets both deep and wide.

Obviously, the heedful man, knowing the direction in which happiness should be sought, will readily try to “dig up the root of” suffering. Now, in digging, one has to have some tools and one has to know the method in which these should be used. The land, in this case, is one’s own heart, which is a bit of rough ground if ever there was, hardly ever cultivated, and besides the odds and ends of rubbish tipped on the surface which can be seen, the whole plot is riddled with every sort of weed and pest lurking underneath. Not the sort of ground a gardener would choose perhaps? But then we are not in the position of being able to choose. Unlike worldly gardeners, we ourselves have dumped the surface-rubbish just recently, and in past times we have allowed the thistles, twitch and bindweed to grow luxuriantly. So we have only to blame our own heedlessness that in the past we allowed things to get in this state. For our cultivation in Dhamma, the Exalted Buddha has provided us with three principal tools with which to “dig up the root of suffering”. These tools are called: Moral Conduct or sila; Collectedness or samadhi; and Wisdom or pañña. They may be rusty from long neglect in which case ’elbow-grease’ will be needed for polishing them up. This elbow grease is called ’effort’ or viriya and we shall never be able to wield these tools successfully unless we can see to it that the mental factor of effort is always present. And effort, of course, is one aspect of this heedfulness praised by all the Buddhas and Arahants, praised by all wise men everywhere.

Now that we know what the tools are, we must get to know the method. Digging is something of an art and digging up craving is the very subtlest of all arts. The method to be used is called “practising Dhamma according to Dhamma”. Here the word, Dhamma has two meanings. In the first case, it means the various methods and ways adopted while training oneself. These methods may be given one by a Teacher in this tradition but one still has to apply them for oneself. But ’Dhamma’ in the second case means both the Law and the Goal. The way is to practise whatever one knows of Dhamma in oneself. This is the work which the heedful man sets himself to do. He has the tools of Moral Conduct, Collectedness and Wisdom and he has the instructions on how these are to be applied. If he lives far from Buddhist lands, these instructions will be the recorded words of the Exalted Buddha as preserved in Pali and translated into various modern tongues. But if he stays in a Buddhist country, these ancient instructions can be supplemented with living example and teaching of those who partly or wholly, have dug up “the root of suffering”.

This root of suffering, this craving, goes down very deep, and like a gardener, the heedful man will have to dig deep using the three tools provided. With each tool he can clear the ground to a certain depth. For clearing the surface of rubbish he will want to use Moral Conduct or sila, for when this is used, the surface rubbish of bodily misconduct and verbal misconduct can be carted off. The Five Precepts or the Eight Precepts which are guides for the practice of Dhamma upon special days of training such as the Uposatha, or the Ten Precepts of a novice, or the many rules practised by monks, all these have as their function, the restraint of the body from evil acts and the restraint of the tongue from evil speech. This outward rubbish may be swept away by sincerely keeping the Precepts, whereby a certain gladness will be experienced born of making effort and from seeing the success of one’s efforts. By digging deeper with the tool called Collectedness, which means all sorts of meditative practice, the fibres of this craving-root, called the five hindrances, may be removed. These five hindrances block the way to the experience of the states of concentration (jhana) and must be removed before the concentrations can be experienced. These five are as follows: sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, distraction and worry, and lastly, scepticism. The heedful man is one who can suppress these at will and enter into the far-ranging concentrations. The tool of wisdom or pañña, is needed to dig out the finest and deepest of roots connected with this craving. These fine roots ranging very deeply are called the pollutions or asavas. Three of them are usually listed: the pollution of sensuality, the pollution of becoming, and the pollution of unknowing. Craving here takes these three forms—that is, the attachment to even subtle sensuality, the attachment to more and more of life—more and more of and pollution of not knowing the truth about this mind-body, not knowing that they are unstable, unsatisfactory, and do not make up a selfhood. These pollutions are a stench in the hearts of all beings who have not experienced Enlightenment and they flow into and infect all the operations of the mind, giving rise to the polluted-mind, unable to know correctly and certainly.

Very briefly here the range of “the root of suffering” has been outlined. Everyone can make a start with this digging, while if one has made a start already, then what about making greater effort? It is important though that this training in Dhamma must be undertaken in the right way, in the way according with Dhamma and this means not according to what one thinks and wishes to do for oneself. As this idea of ’self’ is born of unknowing and craving, it will be no good training in Dhamma according to one’s own ideas. The whole training must be undertaken in the spirit of Dhamma which leads away from craving. Indeed, in the third line of the verse above we see this clearly: “By day and night give up things dear”. This is the way of the heedful man who wishes to practise Dhamma according to Dhamma, for the overcoming of craving, for digging up that root of suffering. This is called ’renunciation’, the very opposite direction to the craving driving most people in this world. In starting to practise renunciation, charity and generosity should be cultivated, thereby freeing to some extent tile heart from meanness. But here, more than this is implied, for it is said: By day and night give up . . . “ This does not refer to the beginning of renunciation but this teaching reaches up to Enlightenment, to the final goal of Buddhist endeavour, that is: ’Who are not heedless, they dig up the root of suffering”. These are the instructions to arouse one to do something about oneself and the method to be used follows in the next line: “By day and night give up things dear”. Before we can do this, we must know what the Exalted Buddha means by “things dear”. By this he means everything for which we have attachment, beginning with the six sense bases themselves: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind; to the six sense objects; sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, and mental stimuli, and then on through the six impressions upon these senses, and so to the six kinds of thought about these sense impressions, and finally to the six sets of craving arising with respect to the six objects. All this and more, for it has been simplified here, and all the world known to us, including all of what is thought of as ’self’, all this inside and outside, is called “things”.

If we would “dig up the root of suffering” then it is obvious that we must be able to renounce attachment to these senses and sense-object and so on. To the heedless man, indeed, this must seem like total annihilation but then he revels in this world and plants in himself “the root of suffering”. He has no deeper view, he has no path to make progress on.

But for the heedful man who has Dhamma as his guide, Dhamma as the lamp which lights his life, this renunciation can be made since he views the things of self and of the world in the light of the last line of the verse: “Deathly, sensuous, and very hard to cross”. Because of this the heedful man thinks that it is worthwhile to train in Moral Conduct, Collectedness and Wisdom and makes efforts with his own training accordingly. The instructions have now been given and the method also, and now to spur us onward, there is the warning: that “things dear” are “Deathly, sensuous and very hard to cross”. We should understand what these terms mean so that we feel roused to practise Dhamma wholeheartedly. There are first, the dear things of death, meaning that wherever craving has its roots, with attachment and clinging, there death will also take its toll. For there is no birth and death if there is no craving, while the more that things are dear to us, whether internal or external, sentient or insentient, the more of birth and death with all its accompanying dukkha we make for ourselves. By clinging to people, places and experiences, even people near to the end of their lives ensure that they will be born again. But this process of craving goes on for most people day and night and they thus ensure for themselves an endless round of birth and death, that is, unless they take up this path of renunciation. To practise Moral Conduct, one must renounce the pleasures which some people seem to get from bodily misconduct such as killing sentient beings, and from verbal misconduct which means such words as lying and slandering. And more renunciation is necessary if one would cultivate one’s mind One cannot develop in mindfulness and concentration and at the same time indulge to the full in worldly pleasures. These have to be given up if the deep states of collected meditation are to be experienced. And the cultivation of wisdom means the renunciation of attachment to the various sorts of defilement which afflict the heart. The more one is able to renounce the influence of the passions and defiling tendencies of the mind, the more will wisdom grow in the heart. In this way, renunciation of “things dear” by the heedful man leads away from the snare of death and leads him towards the Deathless State of Nibbana.

Then again, these dear things are described by the adjective “sensuous”. This is an imperfect translation of the Pali: “amisa”.

This word cannot be rendered by any one word in English but could be defined as “material objects, internal and external to ourselves as perceived by our senses and stimulating various feeling.” Thus the word covers both the external stimulus and the internal reaction to it. That heedless fellow is bogged down in a morass of amisa, of all this enjoyment, of all this bewailing due to materialism. But the heedful man takes care not to be drawn into the bogs of attraction and repulsion and by his heedfulness, his heart need not be spattered by even drop of mud. The heedful man, praised by the Buddhas and all wise men, well knows the dangers in amisa, that entangled with it men’s views are distorted and restricted, and that they are driven to birth and death as dry leaves driven along the ground by the wind.

Lastly, these dear things are called “very hard to cross”. The heedless man has no hope of finding a way beyond those dear things of death and materialistic pleasure. Even if he wished to find some way beyond his restricted and petty existence bounded by these things, there would be no way for him to go until he abandoned heedlessness, and practising became vigorous, mindful and of increasing wisdom. But those who are heedful and practise whatever they can of Dhamma, their crossing over the ocean of this involvement with things and pleasures their crossing-over the ocean of birth-and-death, becomes quite easy. As they cultivate renunciation so heedfulness grows in them with its three aspects of effort, mindfulness and wisdom, and they come through this to the Other Shore which is called the Secure or Nibbana. Heedfulness is the way to Deathlessness, for Nibbana is the experience of No-death, no birth and no dukkha. It is as the Exalted Buddha has said in another verse: “Those heedful ones they do not die, the heedless are like unto the dead”. Now, concerning ourselves, in this matter we are free to choose whichever class we like. No one can compel us to be heedful, or to be heedless. The Exalted One has certainly never ordered people to be heedful rather than the opposite. His own life is the best example of this heedfulness. Let us look at it.

After He left the comforts and security of His palace and took up the ascetic life, he was an unrivalled example of heedfulness. No one has ever made such great efforts as He made in the six years during which He practised extreme austerity. And when He turned away from this course and attained Perfect Enlightenment, He became known as the Buddha. Effort, mindfulness and wisdom were among the qualities which He had brought to perfection. He had no need to make effort and so on for these were revealed as intrinsic characteristics of the Enlightened State. To the highest degree He displayed effort, mindfulness and wisdom for forty-five years—and why? Out of compassion for people that they might learn the path of happy Dhamma-practice for themselves and in time be able to bring help to others. He walked in stages all the length and breadth of Northern India helping people who wished to be helped with this wonderful Dhamma. His whole life was one displaying effort, teaching all people who wanted to learn until His body was exhausted at the age of eighty. But even upon His deathbed, He has taught those who want to know how to practise the Dhamma way and so find in themselves the Dhamma truth. What words are so stirring as those last phrases uttered by Him as He lay beneath the sweetly scented Sala-trees: “Listen well, O bhikkhus, I exhort you: Subject to decay are all compounded things: with heedfulness strive on!” Even when His body was near to death, He did not forget to exhort His followers to practise heedfulness. His last utterance impresses us that all the compounded things of this life, interior, and exteriors, our minds and bodies themselves are all running down, deteriorating, bound to scatter and fall apart, to be lost.

All things dear and beloved are like this—including ourselves. It is only by making an effort that we can escape from the slime of attachment to all this deterioration. We are deteriorating, our families and friends are deteriorating, our material possessions are deteriorating, nothing that is put together can hope to be permanent. All must fail, all must fall apart, wither and die. So we should not bask in a pleasurable lethargy in this life. There is much to be done. All the time, on every occasion, there is heedfulness to cultivate according to the words of the Exalted One: “By day and night . . .” Not just sometimes, not just when we remember, not just on Buddhist Holy Days, not just in temples, not just in front of Buddha-images, but by day and by night. Day and night we are slipping towards death. And we never know when it will be or how. “Tomorrow death may come—who knows?”, as the Exalted One has said, and it may be only a matter of minutes or seconds away. One who has made efforts to grow in Dhamma, who has secured for himself the riches of heedfulness, the coin of effort, mindfulness and wisdom, has nothing to fear, whenever death may come. But the heedless man, what indeed will help him who has not helped himself? All the time, NOW, is the time for effort, mindfulness and wisdom. Only when Dhamma is practised all the time is there any chance to “dig up the root of suffering”. All the time we can try to “give up things dear” and so cross over Death and materialistic pleasure, over the ocean of craving so “very hard to cross”.

Let us then, call to mind frequently this precious instruction of the Awakened One, that it may be the Dhamma to guide our lives, In Pali the inspired words of the Awakened One are:

Ye ve diva ca ratto ca

Appamatta jahanti piyarupam

Te ve khananti aghamulam

Maccuno amisam durativattam.

And in English they have been translated:

Who are not heedless, they

Dig up the root of suffering

By day and night give up things dear,

Deathly, sensuous and very hard to cross.

May we, through heedfulness, all cross over to the Further Shore.

(Source: BPS, Sri Lanka, BL98. For Free Distribution)

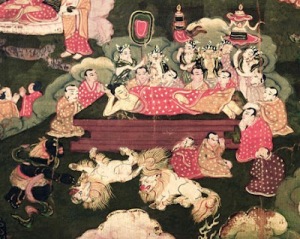

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, some of those gathered around the Buddha broke into tears when he died while others remained composed. Such people usually appear in depictions of the Buddha’s passing. In Japan however, artists illustrating this event often included animals amongst the mourners. I’m not sure why this is so but it is probably because the Mahayana Maraparinirvana Sutra says that ‘all beings in the Triple World wept and wailed’ as the Tathagata passed away. This gave artists the opportunity to use their skill and their imagination to paint a wide variety of beautiful and interesting animals. The first picture below is of a 16th century (Monoyama Period) scroll painting. The next picture is an enlarged section of a similar depiction of the Parinibbana from around the same time. It is clear that the artists delighted in the painting creatures as diverse as centipedes, crabs and molluscs as well as several mythological beasts. The third picture, from a Tibetan thangka, shows two snow lions (gang shenge) morning the Buddha’s passing, an element unusual in Tibetan art.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, some of those gathered around the Buddha broke into tears when he died while others remained composed. Such people usually appear in depictions of the Buddha’s passing. In Japan however, artists illustrating this event often included animals amongst the mourners. I’m not sure why this is so but it is probably because the Mahayana Maraparinirvana Sutra says that ‘all beings in the Triple World wept and wailed’ as the Tathagata passed away. This gave artists the opportunity to use their skill and their imagination to paint a wide variety of beautiful and interesting animals. The first picture below is of a 16th century (Monoyama Period) scroll painting. The next picture is an enlarged section of a similar depiction of the Parinibbana from around the same time. It is clear that the artists delighted in the painting creatures as diverse as centipedes, crabs and molluscs as well as several mythological beasts. The third picture, from a Tibetan thangka, shows two snow lions (gang shenge) morning the Buddha’s passing, an element unusual in Tibetan art.

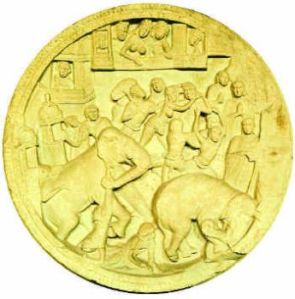

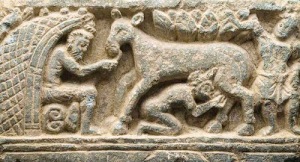

After the biography of the Buddha himself, the Jataka stories have long been most Buddhist’s main knowledge of and contact with the Dhamma. Consequently there are numerous depictions of Jatakas in the art of all Buddhist cultures, and they are depicted in the earliest Buddhist art. The first picture illustrates the Mahakapi Jataka (No.407) in which a monkey king risks his life, and eventually looses it, to save his troop. The piece is a medallion from the Barhut Stupa dating from about 150 BCE. Being one of the earliest examples of Buddhist art the treatment is naive and awkwardly conceived but the story it illustrates would have been immediately identifiable to the viewer. The Alambusa Jataka (No.523) tells of a doe who falls in love with the ascetic who shared her forest. One day he urinated in the river, passing out semen as he did so, the doe later drunk from the river, became pregnant and in time gave birth to a boy. The kindly ascetic accepts the child as his own and helps bring him up. A sexual misadventure in the boy’s subsequent life and his father’s advice concerning it makes up the core of the story. The ascetic, the doe and their child are depicted in a panel from northern India dating from the 4th-5th century CE. Below this is a painting from Dunghuang Cave in western China dated 450 CE depicting the Nigrodhamiga Jataka (No.12). In this story a stag’s willingness to give his life to protect his herd from a king’s frequent hunting expeditions, moves the king to give up hunting and eventually, at the stag’s request, to ban all hunting throughout his realm. The final picture is an illustration from an early 19th century Thai manuscript of the Vessantra Jataka (No.574). It shows Vessantra on his wondrous rain-making white elephant which he is about to give away.

After the biography of the Buddha himself, the Jataka stories have long been most Buddhist’s main knowledge of and contact with the Dhamma. Consequently there are numerous depictions of Jatakas in the art of all Buddhist cultures, and they are depicted in the earliest Buddhist art. The first picture illustrates the Mahakapi Jataka (No.407) in which a monkey king risks his life, and eventually looses it, to save his troop. The piece is a medallion from the Barhut Stupa dating from about 150 BCE. Being one of the earliest examples of Buddhist art the treatment is naive and awkwardly conceived but the story it illustrates would have been immediately identifiable to the viewer. The Alambusa Jataka (No.523) tells of a doe who falls in love with the ascetic who shared her forest. One day he urinated in the river, passing out semen as he did so, the doe later drunk from the river, became pregnant and in time gave birth to a boy. The kindly ascetic accepts the child as his own and helps bring him up. A sexual misadventure in the boy’s subsequent life and his father’s advice concerning it makes up the core of the story. The ascetic, the doe and their child are depicted in a panel from northern India dating from the 4th-5th century CE. Below this is a painting from Dunghuang Cave in western China dated 450 CE depicting the Nigrodhamiga Jataka (No.12). In this story a stag’s willingness to give his life to protect his herd from a king’s frequent hunting expeditions, moves the king to give up hunting and eventually, at the stag’s request, to ban all hunting throughout his realm. The final picture is an illustration from an early 19th century Thai manuscript of the Vessantra Jataka (No.574). It shows Vessantra on his wondrous rain-making white elephant which he is about to give away.

The Buddha taught that there are six realms of existence, one of which is the animal world. (tiracchana yoni). All of these realms constitute samsara, the continually process of birth and death. Indian artists illustrated this doctrine diagrammatically as a wheel of six segments, each showing one of the realms. A single very fragmentary painting of the six realms survives from India, but they are common in Tibet and are painted on the walls at the entrance of most temples. Depictions of the animal world usually show a variety of creatures, domestic and wild, actual and mythological. This is a typically illustration of the animal world from a contemporary Tibetan thangka.

The Buddha taught that there are six realms of existence, one of which is the animal world. (tiracchana yoni). All of these realms constitute samsara, the continually process of birth and death. Indian artists illustrated this doctrine diagrammatically as a wheel of six segments, each showing one of the realms. A single very fragmentary painting of the six realms survives from India, but they are common in Tibet and are painted on the walls at the entrance of most temples. Depictions of the animal world usually show a variety of creatures, domestic and wild, actual and mythological. This is a typically illustration of the animal world from a contemporary Tibetan thangka. As in other religions Buddhists saw certain animals as symbolizing particular things; e.g. the lion nobility and courage, the monkey an undisciplined mind, the goose detachment, and the elephant patience and calm deliberation. They also included animals in their folk tales. One example of this is the story of the three animals who teamed up to reach the fruit none of them could reach individually and who as a result became friends. The story is unique to Bhutan although it was probably a local development of the Jataka (No.37). An animal symbol from China and Japan, and probably of Buddhist origin is the three wise monkeys, now familiar the world over. The most famous and charming depiction of these hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil creatures is found under the eaves of the on the Toshogu Temple in Nikko, carved when the temple was built in the early 17th century.

As in other religions Buddhists saw certain animals as symbolizing particular things; e.g. the lion nobility and courage, the monkey an undisciplined mind, the goose detachment, and the elephant patience and calm deliberation. They also included animals in their folk tales. One example of this is the story of the three animals who teamed up to reach the fruit none of them could reach individually and who as a result became friends. The story is unique to Bhutan although it was probably a local development of the Jataka (No.37). An animal symbol from China and Japan, and probably of Buddhist origin is the three wise monkeys, now familiar the world over. The most famous and charming depiction of these hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil creatures is found under the eaves of the on the Toshogu Temple in Nikko, carved when the temple was built in the early 17th century.

The use of animals as decorative elements in Buddhist art and architecture is as rich as that found anywhere. One of but many examples of this is the procession of animals that the ancient Sri Lankans decorated the semi-circular door-steps (patika) of their temples with. Many different animals are used and in different combinations but perhaps the most common is a continual line made up of elephants, horses, lions and bull. The elephants in these door-steps and elsewhere in Sri Lankan art are depicted most realistically. The example below from Anuradhapura dates from about the 9th century. Under the row of animals is a row of geese (hamsa) with flower buds in their beaks, a motif originating in India.

The use of animals as decorative elements in Buddhist art and architecture is as rich as that found anywhere. One of but many examples of this is the procession of animals that the ancient Sri Lankans decorated the semi-circular door-steps (patika) of their temples with. Many different animals are used and in different combinations but perhaps the most common is a continual line made up of elephants, horses, lions and bull. The elephants in these door-steps and elsewhere in Sri Lankan art are depicted most realistically. The example below from Anuradhapura dates from about the 9th century. Under the row of animals is a row of geese (hamsa) with flower buds in their beaks, a motif originating in India. One Buddhist monument that depicts numerous animals, actual and mythological, in most of their roles, as participants in the Buddha’s biography, symbols, as decorative elements and in illustrations of Jataka stories – is the great stupa at Sanchi, a huge repository of early Buddhist art. Below is a small selection of these.

One Buddhist monument that depicts numerous animals, actual and mythological, in most of their roles, as participants in the Buddha’s biography, symbols, as decorative elements and in illustrations of Jataka stories – is the great stupa at Sanchi, a huge repository of early Buddhist art. Below is a small selection of these.